Those of you who read my articles know I tend to compare technology’s history and lessons with today’s technological impact and growth.

As I mentioned, the Industrial Revolution, the rise of the Internet, and the current AI revolution share similarities. It’s not technology that is predictable; rather, human behavior is what we can anticipate. At the same time, technology accelerates our behavior and deepens the divides in our world.

I started with this paper, “The Rapid Adoption of Generative AI”, and other studies in the field.

As intriguing as they are, not everyone has the time to sift through academic papers. So, I’ve read the studies for you. I’m here to break them down into bitesize pieces so you can read or listen to my summary during your lunchtime or commute.

The data presented is fascinating and has inspired me to go down the rabbit hole. I ended up comparing the data presented in the paper with other economic factors.

Some Food for Thought

Is the rapid adoption of technology favoring particular groups over others?

Could AI widen the gap between the rich and the poor?

Do females have a higher AI adoption rate? The hidden reason behind whether each gender adopts AI or not.

Do young people or the middle-aged population prefer using AI?

Does AI truly correlate with productivity, as suggested by Sam Altman and other major tech CEOs?

Which questions are most relevant to you?

Here we go.

PC, Internet, and AI — Adoption History, the Similarities and Differences.

Here is a bit more historical context: Back in the day before PCs, office workers had typewriters, adding machines, and managing filing cabinets that took up half the room.

Then, the PC showed up in the 1980s. Suddenly, secretaries didn’t need a typewriter anymore; they had WordPerfect. Accountants switched from their calculators to Lotus 1–2–3 or early versions of Excel, allowing people to do what used to take hours or even days in minutes.

In the 1990s, when the Internet took over, office life changed again. It went from writing memos and mailing them across town to sending emails in seconds. People started using early collaborative tools like Lotus Notes and then moved on to web-based tools. Sales reps could access market data in real-time, customer service teams could manage support tickets faster, and it wasn’t just about efficiency anymore — it was about collaborating and being connected.

The accelerating technology adoption rate.

No academics make it easy when they put a figure on paper, of course. Because why don’t you work out the meaning on your own?

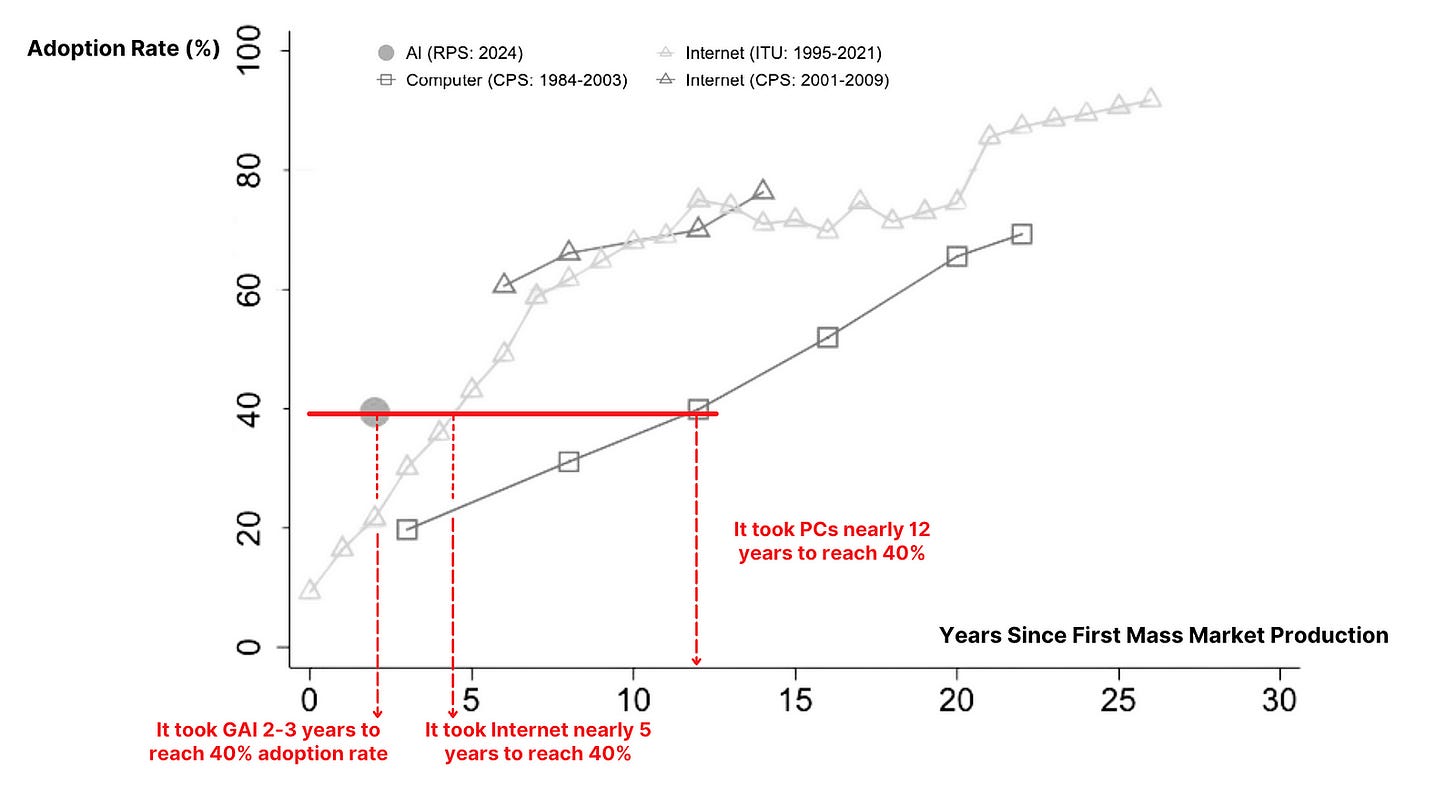

Enough with my sarcasm; let’s use AI’s current adoption rate of 40%, and compare how long other innovations took to reach that level.

Generative AI took 2–3 years to reach a 40% adoption rate in the U.S. That’s incredibly fast. How fast? If we put that in context.

The Internet took nearly five years to hit that same 40% mark.

PC took even longer — almost 12 years before 40% of people had one at home.

Speaking of standing on the shoulders of giants.

Unlike buying a big, bulky PC in the 80s or waiting for a cable company to get the connection to your neighborhood, AI tools are already on devices we all use daily.

Education shows how likely you are to be an early adopter.

As we compare AI adoption per education bracket to computer use in 1984, this seems like a real sense of déjà vu. It’s clear that people with higher education tend to be exposed to new tech tools first.

On top of that, the latest technology will also alter the workplace structure. This is highlighted in The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change, which discusses how computers have pushed jobs toward needing more educated workers.

In another one, White Collar Technological Change, they pointed out that when companies started using more software in office jobs, they also upped the skill requirements.

We find that when firms adopt new software technology, they ask for higher education and experience. Job descriptions increasingly list tasks associated with higher-skill office functions.

In the end, all evidence is feedback on the supply and demand of different education levels.

The salary differences between advanced degrees vs. high school have pushed further away in the last 50 years. The salary of those with advanced degrees has gone up 26%, whereas the wages of those with only high school diplomas have even decreased.

Each new wave of technology didn’t just change what we do — it changed how much we could do. While technology made blue-collar work faster, it often substituted labor with automation or used overseas labor; in short, the demand was balanced by other factors, so the wages remained low.

I believe the trend will continue, and the salary gap between those with higher education and those with only high school will widen.

However, if AGI happens, it will eventually become unpredictable, as predictability involving AGI is extremely low. You can’t predict something potentially more intelligent than you, just like your dog can’t predict your actions.

Anyway, since this is not part of our discussion today, let’s review it in another 10 years.

Rich vs. Poor — Your Boss Don’t Need To Know AI. Because They Have Access To Millions of You.

Let’s talk about tech adoption and income — why do high earners adopt AI differently than others?

This figure shows an unexpected trend: AI and computer use climbs with earnings up to around the 80th percentile, but then the adoption rate drops. Why is that?

If you’re in the top income brackets beyond the 80–85th percentile, you’re likely in a role that focuses on leadership, specialized knowledge, or relationship management.

Think about it: chief executives, surgeons, partners — these jobs are about making strategic decisions, guiding people, or handling complex tasks that require expertise. It’s less about directly interacting with technology day in and day out. Feel free to check the Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics; this wage data primarily aligns with the assumption.

These high earners don’t benefit from using AI to draft emails, take notes, or process data. Their teams do this work for them. AI is great for enhancing productivity in routine tasks, but it still can’t lead a team or perform a highly specialized medical operation.

That’s why the adoption rate dips beyond the 85th percentile — tech tools are great, but they’re not essential for what these high-income professionals do daily. There are no economic incentives for these higher learners to be earlier adopters of new technologies.

And then, there’s the top 1% of earners, which this figure doesn’t even include. These are the CEOs, major investors, or big-time executives. Their earnings come from capital deployment and long-term strategic investments rather than optimizing daily productivity. They need the foresight to steer companies or direct funds for investment effectively.

If anything, people above the 85% tier of earnings normally focus more on getting their employees to learn new technology. That’s why you see a lot of recent news about how CEOs focus on pushing their companies to adopt AI.

The theory is simple. I did the same when I led teams. The more productive your team is, the more projects with higher impact can be undertaken, resulting in more earnings for the company. Again, for the top earners, it’s less about adopting new tools and more about leveraging human expertise and strategic judgment — the kind of skills that AI can’t replace (yet).

Are Older Workers Being Left Behind? Or Is There More?

Generally speaking, the longer you’ve been working, the more skills and experience you build up, which translates to higher pay.

As we just discussed, those with higher incomes also have less economic incentive to adopt technology early on. Their work requires them to focus more on management and specialization.

So, this partly explains why AI adoption rates get lower as age increases.

Of course, factors like younger people growing up with technology make its use a natural part of life. So, it is easy to see a frictionless transition to AI. Another paper also pointed out that junior software developers benefit more from using AI to help them code than senior developers.

It is hard to tell which factor weighs more, as there are many variables in play. I do believe it is essentially economic factors that provide the main drive for adopting new technology.

Gender and AI Adoption: Are Women Being Left Behind?

Back in the 1980s, when PCs were just starting to appear in workplaces, women were actually ahead of men in adopting them.

Why? It’s all about where they worked. Many women held white-collar jobs — think secretaries, administrative assistants, or roles in professional services.

From 1984 to 1989, the share of secretaries using computers jumped from 46% to 77%. It wasn’t about women being more tech-inclined; they were just in the right roles at the right time. These roles benefited most from early computers, involving typing, information management, and communication.

Meanwhile, most men were in blue-collar jobs — manufacturing, construction, and operating heavy machinery. These jobs didn’t have much use for a PC back then. If you’re working with your hands in a factory or mine, you don’t need a computer to get the job done.

Now, in 2024, the story of AI adoption comes in with a 180-degree twist.

The fields that men and women choose to study greatly influence their likelihood of using AI. If you look at the numbers today, many women study Liberal Arts or Humanities, where technology is less central, while men are still more likely to study STEM or Business, which are fields that lean heavily on AI tools.

Take the STEM majors, for instance: Computer Science is 81% male and 19% female. Meanwhile, majors like Music or Nursing — fields more popular among women — don’t require as much daily technology use, which naturally means there’s less reason to pick up AI tools.

Saying that, if we compare men and women in the same occupations, it is a fairer comparison.

Here’s data on Denmark’s workers. I find two particularly interesting pieces of information in this paper, but there isn’t much explanation offered by the authors.

If we just compare among software developers, you can easily see that there are more than twice as many male developers with access to subscriptions compared to females. The same trend applies to the rest of the occupancies in this study. Do women see more important investments for their capital? Or have they acknowledged that generative AI does not help them at work?

“Beliefs about the Productivity of ChatGPT” is on the right, and the “Frictions from Productivity to Adoption” is on the left. Clearly, men believe they are experts in using ChatGPT, while women believe the issue arises from not enough training.

Is it all about having confidence and jumping right in to use new technology?

You see, a lot of media made a fluff about gender inequality in adopting AI.

On the contrary, as a woman, I don’t see an inherent inequality here.

It’s really about the jobs, majors, and personalities. There are fewer women opting for STEM when choosing a subject; subsequently, there are fewer women qualified in STEM-related workplaces. Then there are personalities; women tend to be more conservative when talking about achievement and are more likely to experience imposter syndrome.

Without considering the underlying reasons behind these choices, jumping to conclusions and arguing that something is inherently wrong and needs fixing is easy.

I see little value in trying to balance the AI adoption gender data. Specifically among women, unless we push more girls to pursue STEM or Business degrees instead of Art or Music.

It is more important for us to ask: What are we trying to achieve? Why should we force the economy and society to address a “problem” that may not even exist?

The key isn’t necessarily to provide specialized AI courses, which are everywhere. It is about recognizing that job demands drive adoption. Right now, those demands are primarily based on the fields that men and women choose to enter.

Are the productivity gains from AI as significant as they seem?

The paper’s estimate of AI’s impact on productivity —

If we assume that generative AI increases task productivity by 25% — the median estimate across five randomized studies — this would translate to increase in labor productivity of between 0.125 and 0.875% points at current levels of usage.

Well, but this sounds very abstract, isn’t it?

Imagine you’re working on a task that takes typically 8 hours. If AI improves productivity by 0.125 percentage points, it’s like shaving off 6 minutes from that 8-hour task. On the higher end, 0.875 percentage points would save you 42 minutes.

While this might sound small, multiply it across a whole team, a company, or even the entire industry, and those saved minutes can quickly add up to significant time savings.

AI could be a big productivity booster, but its impact is not always as instant or dramatic as people expect. It depends on how it’s used, the workers involved, and how ready organizations are to embrace it.

It’s a bit like getting a shiny new kitchen appliance — sometimes it makes cooking faster, and other times it adds more steps because you’re still figuring it out. About 80% of people said they spent more time learning the tool and double-checking what it produced.

Also, a paper proved that AI is not a productivity booster for software development, as CEOs like to think. Let me know if you’d like me to break down this paper.

Like any new gadget, there’s a learning curve. Companies are facing a lag in getting AI fully integrated.

The problem is, many CEOs are caught up in the hype of AI. They focus on adopting AI or developing capabilities just because it’s the trendy thing to do, rather than understanding the real needs of their users. It’s like Google’s AI Overview — it’s a shitshow that can not satisfy even the basic user intent, as I’ve discussed in my other articles.

The truth is that AI applications are evolving so fast that providing training on specific tools almost seems pointless. When employees master one tool, there’s a new one on the horizon. Instead, what’s genuinely crucial is fostering a problem-solving mindset within teams. That way, employees can quickly integrate it into their workflow no matter what shiny new AI tool comes along. It’s not about the tool — it’s about the adaptability and readiness to make it work.

AI adoption exacerbates workplace inequalities?

For workers, it’s easy to think that learning more skills is always the best move for your career — it’s intuitive. But we often forget that time is limited. You can’t learn everything, and you have to be strategic about what’s worth your time.

For me, being familiar with AI has been incredibly useful — it’s like having an extra set of hands. But I can’t confidently say the same for everyone. Not every industry benefits equally from AI, and it’s not a one-size-fits-all solution.

We should be careful with the hype around learning AI. It’s a bit like when people who code said everyone should know how to code. Honestly, it’s the same kind of blanket statement — well-meaning but often impractical. My aunt thinks everyone should learn code, too. Sorry, auntie, but that’s just not realistic.

As we see more extreme comments about how AI will shape our future — for better or worse — remember that problem-solving skills and the ability to build genuine connections are probably more important.

How Might AI Influence Growth and Inequality? Until Next Time

It is not easy to conclude AI’s impact on different types of inequality in our overall economic activities. But generally speaking, I think the following are the subjects that we should all have a think about.

Innovation Boost? Can AI drive innovation, creating new products, services, and markets? No, AI can’t drive any of these, that’s up to YOU.

Efficiency Gains? Automation and AI can improve efficiency? Yes, it largely depends on the industry and the specific task to be improved.

Skill Polarization and Salary Gap: Demand for high-skilled workers may increase. What’s for sure is the salary gap will widen.

Wealth Concentration: Benefits of AI might accrue to companies and families who invest in or control AI.

There are topics that I haven’t touched on today. One of the more interesting ones is Global Disparities; countries adopt AI at different rates, which I suspect will largely affect the future of a macroeconomy and geopolitics.

I also didn’t talk about policy intervention. I fundamentally do not believe it is smart to wait for the government to intervene or regulate. Our government is becoming heavier and more redundant than ever; the more we ask the government to do, the less efficient they become.

Next, “Does AI Make Software Developers More Productive?”

Share this post